Abstract: This article explores the transformational character of solidarity economy network communication in Portugal and Catalonia, focusing on the first two months of the crisis brought on by COVID-19. We assume that what these networks choose to convey (or remain silent on) in their public communications reflects their positions in the fields of action and values and their theoretical alignment, establishing an ethico-political orientation. Through the analysis of virtual content conveyed by solidarity economy organisations, we analyse the topics covered, the types of content and sources cited, and the level of demand in the discourse, as well as their individual, institutional and collective character. The results reveal very different communicative approaches in each of the cases analysed: from silence or total absence of communicative practices to what can be considered a transformational praxis communication, based on collective action challenging the structures of power and domination and pointing out ways to overcome them. The article proposes a transformative communication radar linking Habermas’s theory of communicative action and Fuchs’s Marxist-inspired praxis communication concept, as a way of distinguishing merely instrumental communicative approaches from those guided by communicative and cooperative rationality driving new agreements and societal transformations.

Keywords: solidarity economy networks, praxis communication, communicative action, content analysis, COVID-19

Acknowledgements: This work was supported by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia – FCT (Science and Technology Foundation, Portugal) through a doctoral scholarship under Grant Agreement no. SFRH/BD/136809/2018. The translation was supported by FCT – Foundation for Science and Technology, within the scope of UIDB/00727/2020. We are grateful for having discussed a preliminary version of this study at the Network Society Today workshop (November 2020, IN3-UOC, Barcelona) as well as for comments received from anonymous peer reviewers, which have contributed to improving the presentation of the results and the discussion of this article.

1. Introduction

This article analyses the communicative response of formal solidarity economy networks in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Portugal and Catalonia.

The global spread of the disease in early 2020 created an unprecedented emergency situation, with people confined to their homes and most of the global economy shut down.[1] The imposition of social distancing forced a reorganisation of life in society whose effects and duration were yet to be known. The configuration of the ‘new normal’ placed the digital sphere in an even more central position, providing virtual spaces for work, teaching, learning, exchange, socialisation and culture – as well as for social mobilisation and political demands (Fuchs 2021). As the COVID-19 pandemic expanded, numerous solidarity and mutual aid initiatives began to emerge, providing food, equipment, domestic support and more (Blanco 2020; Georgiou 2020; Solnit 2020; Spear et al. 2020). While many of these initiatives arose as spontaneous acts of mutual aid between neighbours, citizens and ordinary people willing to help in different ways, others came about as a result of the work of existing organisations and networks already underway (Estivill 2020; Hespanha 2020). Solidarity economy networks have played an important role, especially in the last two decades, in the promotion of alternative models of work and consumption, production, exchange and care, bringing together a wealth of experiments concerned with social and ecological justice, collective action and systemic transformations (Castells 2012).

Knowing that “networks are created not just to communicate, but also to gain position, to outcommunicate” (Mulgan 1991, quoted in Castells 1996/2009, 86), the role of information and communication technologies has become central in promoting and (re)producing the work of these solidarity networks in advancing alternative ways of organising life and livelihoods away from the capitalist market. The informational and communicational trail these networks leave behind in the digital realm provides fundamental data for understanding what claims for socio-economic transformations are being put forward, and by what means.

The aim of this article is to explore how formal solidarity economy networks used online communications to promote their mission to transform the dominant socio-economic model in the face of a crisis with profound impact on societies and the economy. To achieve this, the study develops a comparative approach based on content analysis and proposes a radar of transformative communications derived from the type of content and themes conveyed by solidarity economy networks and how these relate to the concepts of communicative action and praxis communication as transformative approaches to the lifeworld.

The following section introduces the theoretical framework guiding the analysis. This framework is based on Habermas’s theory of communicative action and Fuchs’s concept of praxis communication. The article then presents the methodological approach and analytical model developed for the specific cases of the study. The results section puts forward the communicative approaches of both networks, revealing the type of content conveyed, their common sources and the main themes addressed. Finally, the article concludes with a brief discussion on the transformative potential of different communicative approaches.

As happened in other periods of crisis which gave rise to a myriad of solidarity economy initiatives aimed at addressing people’s needs while questioning the dominant economic model (Castells 2017), the COVID-19 crisis opened a new wave of mobilisation. This study contributes knowledge on different strategies already in place, which may be useful for politicians, practitioners and scholars alike.

2. Networked Communication Practices, Communicative Action and Praxis Communication

The penetration of information and communication technologies in recent decades into practically every sphere of human life in a globalised and hyper-connected world has led to profound changes in the organisational logic of society. By the end of the twentieth century, networks had become the basic social morphology of the new Information Age (Castells 1996/2009). Technological advances created the conditions for the emergence of a Network Society that enabled a restructuring of capitalism in the form of a “global informational capitalism” which no longer depended on space and time for its capital and labour flows. As “information has become the key ingredient of our social organisation” (Castells 1996/2009/), control or influence over communication is the main form of power in the Network Society (Castells 2007).

Taking on the “opportunity offered by new horizontal communication networks of the digital age” (Castells 2007), new forms of counter-power, social change and alternative politics have also emerged. Solidarity economy networks, in the form of institutional organisations guided by principles of cooperation and social and ecological justice, assume a vocation of criticism of the capitalist economic system. The phenomenon of the solidarity economy has roots in new social movements arising from the economic crisis of the mid-1960s and 1970s, and began to emerge in Latin America, France and the Azores in the 1980s, although “initially without a shared conscience” (Estivill and Miró 2020, 71). The solidarity economy emphasises the specific nature of new initiatives and logics that differ from those of the established social economy organisations largely instrumentalised by the State, particularly in southern European countries as a consequence of the regression of the welfare state, which used organised civil society as a partner in the implementation of social policies (Monzon and Chaves 2012). From Laville and Gaiger’s perspective, the solidarity economy is expressed by “the socialisation of productive resources and the adoption of egalitarian criteria” (2009, 162) and presupposes a double political and economic dimension (Laville 2009, 42-43). Reaffirming the original principles of social economy, the solidarity economy offers an alternative project of society with a political stance, highlighting the need for a commitment that promotes emancipation and democracy, empowering people and creating decent socio-economic alternatives.

Public communication is established as a means of action for such economies, in the sense that the practice of solidarity economy networks in the public space is oriented towards transformative action while defending values and principles which are radically different from those guiding contemporaneity. Solidarity, sustainability, inclusion, cooperation and social emancipation oppose the dominant model based on competition, exploitation, compulsory accumulation and exclusion.

Habermas’s (1962/2012) theory of communicative action offers a positive view of modernity concerning the possibility of a public sphere in which collective voices may emerge in order to influence the contractual parameters of the system in the construction of democratic societies. As language fulfils the functions of understanding, coordinating actions and socialising individuals in the system (Habermas 1987), communicative action allows a rationalisation of the lifeworld. Habermas believes in the human capacity to act beyond selfish instincts and affirms the rationally humanising condition of humankind (1962/2012).

However, there are no communication domains exempt from the influence of power (Habermas 1962/2012). Economic power triumphs and national states become hostages to financial, material and knowledge flows. Basic state obligations under the old social contract submit to the market. Thus, Habermas mobilises the concept of the colonisation of the lifeworld and relates it to the pathologies of modernity. Modern subjects yield their lives to market laws and state bureaucracy. Such apathy reinforces dissociation trends, allowing the economy and the state to be controlled by a minority that sets the rules without consulting the majority. But the system is not a closed sphere; it has cracks and flaws (Mance 2008), and alternatives emerge, as evidenced by the appearance of new social movements. In fact, Habermas (1962/2012) sees contemporaneity as the great confrontation between the system and the lifeworld. While the first always seeks to keep the second invariable, in the lifeworld, interacting actors establish other values and conformations that influence society. This does not occur without contradictions and violations, but it is also done with the enthusiasm of those who believe in the rational power of communicative sharing.

The ethico-political character behind human action reveals its transformative potential regarding the lifeworld (Gramsci 1970; Bernstein 1979). Fuchs introduces the Marxist concept of ‘praxis’ – referring to “political practices whose goal is a human-centred society” (2020, 338), or in Freire’s terms, “reflection and action directed at the structures to be transformed” (1970, 162) – to argue that “only when objective contradictions trigger the collective political organisation of protests and movements that aim at progressive changes is there a chance for the establishment of a better society” (Fuchs 2020, 338). According to Fuchs, “communication is not automatically […] a means to question domination”, but it may be considered praxis communication once it is used in the public sphere with a critical intentionality. As “a practice through which humans create and reproduce social relations”, communication may or may not imply a collective consciousness that questions the dominant powers and enables the formation of alliances and shared objectives. For Fuchs, “social struggles and political action can transform communicative practice into praxis communication” (2020, 339), as long as one is aware of the objectives and the path to be followed, as well as the action plan built to achieve that effect. The use of information and communication technologies will be one of the most powerful instruments of struggle in the twenty-first century.

In this article we pose the question: to what extent can the communicative action of solidarity economy networks be considered praxis communication? Our proposal is to explore how contemporary networks that propose socio-economic alternatives make use of communications to advance and practise their missions: in other words, how they use social networks to inform their participants/members, communities, groups and citizens and also how they mobilise them towards the construction of an alternative economic and social model.

3. Methodology

The study we conducted comprises a qualitative analysis of Portuguese and Catalan solidarity economy networks’ communications on social media during the first two months of the COVID-19 crisis. Through content analysis methods, we explore the online communication channels of the Catalan Xarxa d’Economia Solidària (XES), Rede Portuguesa de Economia Solidária (RedPES) and the Azorean Solidarity Economy Regional Cooperative (Cresaçor), providing insights into their communication strategies to promote the solidarity economy as an alternative model to the dominant socio-economic system.

Based on the observation of online platforms and the analysis of social media content, we analyse the message the networks convey in the public sphere and reflect on their ethico-political character.

The research is also informed by previous ethnographic fieldwork in Portugal and Catalonia (Pink et al. 2016) as part of broader research on alternative economies and the communication commons in both regions. From a Habermasian perspective, the current researchers have been working over time (and space) on the lifeworld of the two networks which are now the object of study in the online world.

Known for its vivid solidarity economy ecosystem (Estivill 2018), Catalonia is a paradigmatic model to juxtapose with a neighbouring region where solidarity economy practices are not so rooted (Hespanha and dos Santos 2016). The present comparative study hence departs from a non-comparability term-to-term (Maurice 1989, 185) and is based on a societal approach which recognises that the same categories can have divergent meanings for each societal space.

All data quotation in this article is translated by the authors.

3.1. Case Selection

The selected cases refer to the Portuguese and Catalan solidarity economy networks, RedPES, Cresaçor and XES, all members of the Intercontinental Network for the Promotion of Social and Solidarity Economy (RIPESS Europe).

The interest in

studying

these cases is justified by the intense institutional relations that

have been

established between the networks of the two countries. The Catalan

network is

the closest international partner of the Portuguese network and has been

identified as a model for the development of RedPES.

This proximity, which is also cultural and territorial, results in

regular

relations between members through participation in seminars and

meetings,

invitations to fairs and conferences, and frequent visits between

members of

both networks.[2]

On the other hand, Cresaçor is considered

the key

organisation of the pioneer solidarity economy experience in Portugal,

justifying the analysis (Amaro

2009).

The Catalan Xarxa d’Economia Solidària (XES) is composed of more than 400 members (individuals and collectives), and brings together 19 local networks (either active or in development) throughout the Catalan territories, according to data from 2019 (XES 2019). XES was founded in early 2003, following a process which started in the mid-1990s in preparation for the first World Social Forum in Porto Alegre in 2001. The network has the legal form of a non-profit association with the aim to “promote and extend [the] solidarity economy” (XES 2013), including cooperativism, fair trade, solidarity, responsible consumption, ethical finance, social currencies, and “any other economic practice based on the values of cooperation, democracy, equality, sustainability and solidarity”, as the XES statutes note. With a professional ‘technical’ structure, the network organises an annual solidarity economy fair (FESC, with 14,000 visitors in 2019), monitors the evolution of the Catalan ‘social market’ (which reported 221 million euros generated in 2019), and has an active political voice. Every year, XES publishes a social balance report on member organisations in terms of socially responsible management practices. The annual XES budget was almost 500,000 euros in 2019.

In Portugal, Rede Portuguesa de Economia Solidária (RedPES) was founded in 2015, initially as an informal network and a few months later as a volunteer-run non-profit association. With roughly 80 associated members (both individuals and organisations), RedPES has a strong presence of academics and affiliated members with a high age profile, some of whom are connected with the Catholic Church and collective movements from the post-dictatorship period in Portugal, which was fertile in terms of cooperativism and self-management. The number of participating (not always affiliated) young people fluctuates. Some of these are students in an ongoing process of fieldwork in the area of social and solidarity economies. RedPES organises an annual meeting on the same day as the general assembly of the association. This meeting brings together academic and professional knowledge in order to construct the solidarity economy project, often with little participation. RedPES is mainly concerned with the foundation of the concept and practices in Portugal and aims at clarifying, informing and creating identity rather than promoting tools for action, an area in which RedPES invests less (Parente 2017, 496) and which seems still to be in an incipient phase of creation.

Although RedPES was the Portuguese case initially selected for this study, its incipient communicative action – confirmed during the data collection phase (Table 1) – led us to select another Portuguese organisation that has a strategic vision for the sector and is an aggregator of common interests that would make viable a comparative approach with XES. The Azores Solidarity Economy Network, Cresaçor, was founded in 2000 as a cooperative, and is itself also a collective member of RedPES. With 27 cooperating members on the six islands in the archipelago, it was born within the scope of the Project to Fight Against Poverty and for the creation of a programme for the development of socio-professional companies in the Azores. Its mission to promote local and community development on the islands enjoys strong support from the regional government, and puts into effect social policies for, among other things, employment, training and the inclusion of immigrants. In addition to the more assistance-oriented aspect, Cresaçor possesses a component for boosting the economy, with incubators, entrepreneurship and a micro-credit office, as well as horticultural production, livestock breeding and the sale of various local products with a solidarity-based economy stamp.

3.2. Data Collection

The

first

phase of data collection consisted of an exploratory approach to the

solidarity

economy networks’ main communication channels, for a general overview of

the

platforms most commonly used (Table 1).

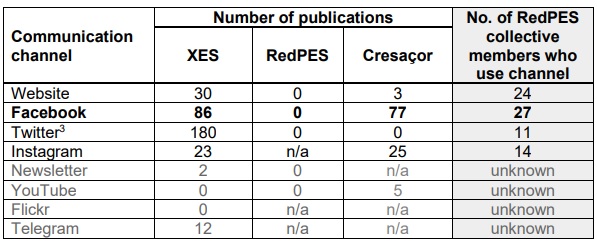

Table 1: Number of publications by XES, RedPES and Cresaçor from 13 March to 13 May 2020 in their communication channels. The grey column indicates the communication channels most commonly used by RedPES members.

Although the absence of content published by RedPES during the period under analysis is considered data per se, in a second round of data collection for this study we resorted to the communication channels of the RedPES collective members,[4] instead of the institution itself. Through online research, we surveyed the communication channels of 27 members and collected the URLs of their websites, Facebook, Twitter and Instagram profiles. From this survey, Facebook stood out as the most commonly used.

We then manually extracted XES Facebook post data from 13 March (the day of the first publication related to COVID-19 by one of these networks) to 13 May 2020 into a spreadsheet, including date, time, content, hashtags and URLs. This resulted in a dataset with 86 posts from XES. Afterwards we observed the Facebook pages of 17 RedPES collective members[5] who used Facebook during the same period, summarising a total of 513 posts for analysis. From an exploratory approach to the dataset, it was possible to identify a member of RedPES that is itself also a solidarity economy network comparable to the Catalan network: the regional network of the Azores, Cresaçor, which published 77 posts on its Facebook page in the same period.

3.3. Data Analysis Methods

We developed a passive analysis of content disseminated by both networks on their Facebook pages, consisting of the study of observed information patterns without active participation or engagement of the researchers (Franz et al. 2019; Eysenbach and Till 2001). Each unit of analysis refers to a Facebook post. All data quotations were translated by the authors.

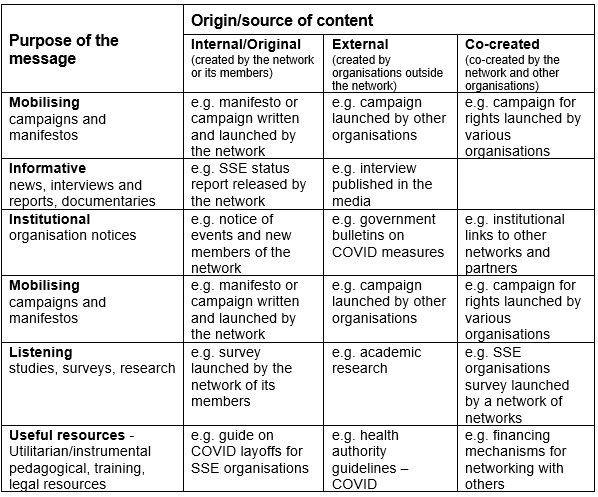

In the first round, data was coded according to the type of content (news, campaigns, dissemination, institutional, manifestos, resources, research), its source (original, external, co-created), and the main topics addressed.

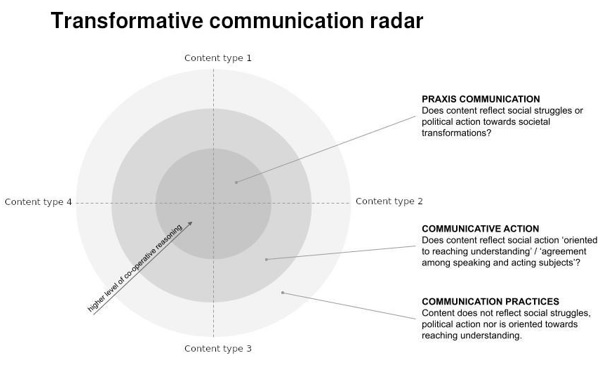

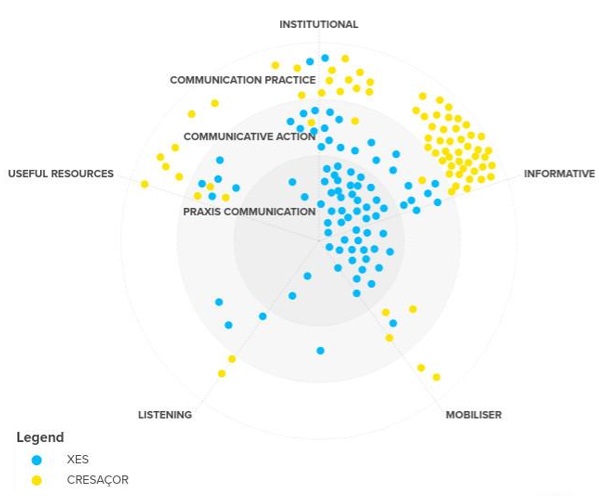

In a second round, data was coded according to its ethico-political character, as summarised in Figure 1. The guiding questions to categorise each unit were:

● Does the content reflect social action oriented towards reaching agreements or understanding among subjects? (Communicative action)

● Does the content reflect social struggles and/or collective political action? (Praxis communication)

Figure 1: Analytical model based on the concepts of praxis communication (Fuchs 2020) and communicative action (Habermas 1962/2012).

Each unit of analysis in Figure 1 is positioned within the radar according to its type (axis) and transformative character (circles). The inner circle contains elements that relate to social struggles and political action; the intermediate circle contains elements with evidence of communicative action; the outer circle contains generic content that can be considered neither praxis communication nor communicative action. Although both categories are mutually exclusive, the radar format brings some coding flexibility due to the relative positioning of the content. For instance, while a media article is unequivocally considered informative content and therefore stands near the information axis, it may tend more towards the institutional axis or towards the mobilising axis. Similarly, content encoded as communicative action, for example, is placed in the middle circle, but depending on whether its substance is considered closer to praxis or practice, it will be positioned closer or farther from the inner or outer circles. Overall, the analysis aims to assess the transformative character inherent to the content disseminated by each network.

In the next section, we present the results that emerged from the exploratory analysis of XES and RedPES communication on social networks. On the basis of a comparative analysis of the different communicative approaches, we first propose a substantive approach to the communication of the two networks through the classification of their content. Secondly, using this characterisation, we systematise the different types of content in a summary table that proposes three levels of gradation of the transformational potential of communication, according to its collectivist/individualistic and demanding/conformist character. The typology makes it possible to distinguish between generic communicative practices (more conformist and individualistic), practices targeting communicational action (which seek to generate new agreements and understandings), and practices aligned with communicative praxis (strongly collectivist and demanding).

Finally, we apply this analytical model to Catalonia’s solidarity economy network, XES, and to the solidarity economy network of the Azores, Cresaçor – which, being a collective member of RedPES, presents a communicative practice that is comparable in analytical terms to that of XES. The comparative legitimacy of these two cases results partly from the fact that Cresaçor is a regional network and, therefore, analogous to XES, which bears territorial impact in Catalonia, making the two more directly comparable (unlike an institutional network as compared to several fragmented collective organisations); and that the existence of communicative practices based on a network logic between Azorean organisations (as opposed to the majority of the mainland collective members of RedPES) has been highlighted. The number of publications from both XES and Cresaçor networks was similar for the period under analysis (n = 87 vs. 77), while the number of publications by the RedPES group of members (around 500) leads to an unbalanced comparative analysis. The present analysis results in a comparative radar that illustrates the transformational character (or otherwise) of the communicative approaches of each of the studied networks.

4. Between Silence and Transformational Communication: Communicative Practices and Praxis in Solidarity Economy Networks

Our analysis explores the constitutive and transformational character of the communicative practices of formal solidarity economy networks in Portugal and Catalonia. We assume that what these networks choose to convey (or remain silent about) in their public communications reflects their positions in the fields of action and values, establishing an ethico-political orientation. We look at the topics covered, the types of content and sources cited, and the demanding level of the conveyed discourse, bearing in mind the individual/institutional and collective approaches of the solidarity economy networks in their communications.

4.1. Substantive Communication Approach: Comparative Analysis Between XES and the Collective Members of RedPES

In our initial approach to the communication channels of RedPES and XES, we were faced with two diametrically opposed situations: while XES presented vigorous, frequent and diverse communication on different platforms (its own website, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter), RedPES maintained silence, its communication channels remaining quiet during the period under analysis. This led us to explore the communication channels of RedPES members instead of the institution itself, in order to discover what kind of communicative practices existed at the nodes represented by the network’s member organisations in the absence of communication from the institutional network.

Table 2 systematises the typology used to classify the types of content conveyed according to their objectives and their origins/source.

Table 2: Types of

content

according to objectives and sources

The

analysis

of each type of content follows from the point of view of XES and the

collective members of RedPES in relation to

the

‘objectives’ criterion of the message.

4.1.1. Mobilising Content

In the case of XES, this category, which includes campaigns and manifestos, is one of the strongest approaches given the number and diversity of campaigns disseminated in conjunction with other organisations, with calls for action, mutual support and solidarity. Of the 86 XES publications analysed, 21 were related to campaigns and 5 mentioned manifestos.

With regard to manifestos, the origin was verified, confirming the existence of both original content written by XES itself, and the adherence to manifestos launched by other organisations and the co-creation of manifestos on the network. The topics addressed in the manifestos published by XES on Facebook called for self-organisation and consumption of locally sourced products; support for peasants and existing networks in rural territories; opposition to the ban on frequenting allotments during confinement; the demand for a basic and unconditional income for cultural workers; and the “end of an economic model that favours the accumulation of profits by large multinationals and marginalises small businessmen, small producers and, above all, workers” (XES, May 9, 2020), in defence of fair trade and the solidarity economy.

With regard to campaigns, topics revolved around different social rights, such as labour, housing, access to food, the rights of migrant people and the defence of public health. Support was also identified for initiatives by farmers and meat producers, in defence of the “Agroecological Supply”, small businesses, cooperatives, and the supply of electronic equipment for remote education. Fundraising campaigns through crowdfunding platforms were also found. Like the manifestos, the campaigns published by XES on Facebook show different sources: original XES content, external initiative campaigns to which XES adheres, and campaigns co-created with other entities.

In the case of

the

collective members of RedPES, there were

mainly

individual campaigns dedicated to specific topics amongst the

organisations’

activities, such as the rights of diabetic people, the needs of nursing

homes

and the tourism crisis. However, there was a regional sub-network in the

Azores

making advocacy efforts to promote the solidarity economy through the

#CORES

campaign, which unites several local businesses. A campaign was also

identified

in the Algarve region that demanded public measures to support

agriculture.

However, no original manifestos were found in the content released by

the

collective members of RedPES.[6]

4.1.2. Informative Content

With regard to the dissemination of news and news reports, there was a fundamental difference between the two organisations in the type of sources chosen: XES almost exclusively uses independent and alternative media (such as the newspapers La Directa and El Salto), whereas members of RedPES select mainstream media (such as public television and the main newspapers) as the main sources of news.

This difference in the choice of sources results in very different actors for the issues addressed: on the side of the organisations that make up the Portuguese network, these include the voices of public authorities, politicians, commentators, celebrities and major international organisations such as the UN; on the XES side, the voices of activist figures and researchers are promoted, and these are often members of the network themselves who have been gaining media space, even if in the so-called ‘alternative’ niche media, whether through columns and articles or in commentary or interview format.

The topics reported are also generally very diverse. XES exclusively publishes news related to socio-economic and environmental issues, problems of the dominant economic model and transformational proposals for overcoming them, establishing links with a global movement present in different geographies, particularly the global South. In the content analysed, terms and expressions such as capitalism, productivism, consumption, crisis, solidarity, dignified life and “life in the centre”, care, needs, sharing, labour, workers, transforming economies, ecological transition, relocation, climate, environment, growth and degrowth, cooperation, renewable energies and carbon emissions were frequently found. There was a strong focus on agroecology topics, such as agroecological supply, peasantry, farmers and producers, territory, rurality, proximity, ecofeminism and self-consumption.

In the case of members of RedPES, the main topic in focus during this period was generally the health crisis itself, with frequent disclosure of bulletins from the government, the General Directorate of Health and local government authorities. In the content analysed, mention was made of topics such as subsidies, debt, care work and nursing homes. Some sensitivity was also noted for environmental and climate issues, expressed in terms of global warming, pollution, water and renewable energies, and for agricultural issues such as markets, farmers, local and organic produce, and pesticides. Mention is made of degrowth, local currencies, fair trade, sustainable consumption and sex work, as well as other topics not strictly related to the social and solidarity economy, such as the dissemination of religious content (Easter and Santo Cristo dos Milagres in the Azores), and the celebration of international days.

4.1.3. Institutional Content

Institutional content mainly comprises the organisation’s notices, from news of fairs and events to welcoming new members who are part of the networks.

Notices about cancelled events or altered opening hours were frequent, especially on the Portuguese side. RedPES members focused their communication on responding to the specific pandemic crisis, but also announced services, products from the organisations themselves, personal stories and institutional acknowledgements to partners and funders.

In the case of XES, there was regular dissemination of content on activities organised by the network itself or by its members, as well as the announcement of the admission of new members. It also celebrated the 25th anniversary in 2020 of the state network of which it is a member, the Network of Alternative and Solidarity Economy Networks (ReAS).

4.1.4. Listening Content

The networks disseminate and call for participation in different types of studies, surveys and research projects. In XES, this type of content is usually disseminated with the aim of listening to the members of the network themselves and their needs and offers. The data collected enables the development of new proposals and initiatives that affect members. The themes identified include the design of public policies in response to COVID-19, the need for cooperative financing for social and solidarity economy organisations, and community practices in the social and solidarity economy. Here, too, the origin of the surveys is diverse and includes content created by XES or its members, or co-created with other entities.

In the

Portuguese case, this

type of content is usually external to the organisation, originating

within

academia and dealing with social issues related to gender equality,

domestic

violence, child poverty and other themes lacking any connection to the

social

and solidarity economy.

4.1.5. Useful Resources

In the case of XES, here we include resources considered useful for its members, created by XES itself or by grassroots organisations. For example, a cooperative of lawyers, a member of XES, developed a series of materials on the labour implications of the exceptional situation created by COVID-19, answering questions about teleworking and other work and health implications for companies. XES also developed a series of recommendations on how solidarity economy entities could deal with layoffs without “reproducing capitalist logic”. Another example was the sharing of an SSE Trivial game, as a “get-away” resource in times of great digital activity, and the sharing of materials “for a feminist lockdown”.

In the case of collective members of RedPES, this type of material consisted mainly of recreational and educational materials for families and children (games and exercises to do at home, for example), as well as resources created by public authorities on nutrition, health, safety and hygiene, among others.

As Fuchs (2020,

339) stresses, “communication is not automatically

‘good’” just because it exists, and the previous characterisation

confirms that

the same type of content can be viewed and appropriated in very

different ways,

with a greater or lesser degree of a demanding, collective, critical

perspective.

4.2. An Approach to the Transformational Potential of Communication: A Comparative Analysis Between XES and Cresaçor

The previous analysis of the different types of content, sources and topics published by XES and by the collective members of RedPES on Facebook brings us to the next phase, in which we classify the different types of content according to the proposed transformational potential.

For reasons of comparative legitimacy and the operationalisation of the analysis itself, we chose to consider Cresaçor on the Portuguese side for this phase, and not the grassroots organisations or the collective members of RedPES.

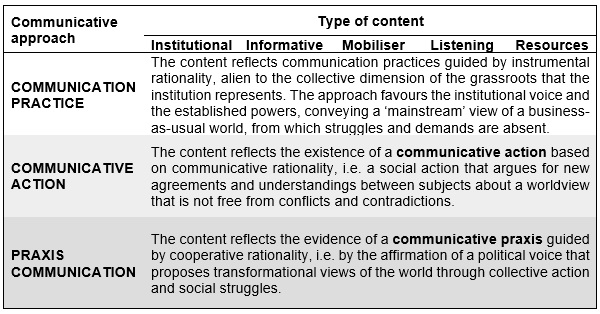

Communicative approaches were classified into three degrees, hierarchically ordered according to the level of conformism or content transformation, as summarised in Table 3.

Table 3: Communicative approaches according to the conservative or transformational nature of the content

The content was classified according to type and transformational character, taking into account the criteria presented in Table 3, and positioned on a radar of transformational qualities of communication that advance towards the centre: in the outer circle is found content referring to generic, merely instrumental communication practices; in an intermediate circle is found content associated with communicative action; and in the centre is found content that reveals a communicative praxis with greater political, collectivist and transformational influence. Figure 2 illustrates the application of the model to the cases.

Figure 2 - Transformational communication radar applied to XES and Cresaçor content analysis.[7]

The

communication

radar shows that Cresaçor tends towards

generic communication practices, while XES shows an orientation both

towards

communicative action and towards the praxis of a critical and

collectivist

nature, placing the Catalan network at the centre of the

transformational

communication radar.

4.2.1. Praxis Communication

All the content classified as praxis communication in this study originates from the Catalan network, beginning with the first COVID-19-related publication for the period under analysis, which referred to a manifesto released on 13 March (XES 2020a) that read: “‘Neither the ultimate cause of the coronavirus nor the way to deal with it is alien to the capitalist and productivist patriarchal system that we suffer from’. Care, solidarity and dignified lives: XES manifesto in the face of the Covid-19 crisis” (XES, March 13, 2020). This was the first of 50 publications in two months to reflect the affirmation of a political voice that proposes transformational views of the world through collective action and social struggles. Almost always through mobilising publications, though also through informative and institutional content, this praxis was based on communication campaigns of which the “solidarity pandemic” (#PandèmiaSolidària) was perhaps the one with the greatest reach and visibility, as it was disseminated nationally in order to reference solidarity responses to the COVID-19 crisis, such as those featured in an article published by El Salto, “More Mutual Aid and Resistance in Times of Coronavirus” (Cabot 2020), with “several initiatives of resistance to #Covid19 in most of which we [XES] participate either as a network or through some of our members” (XES, April 18, 2020).

The “social shock plan” (#PlaDeXocSocial) was another example of a campaign promoted by XES with a national scope, demanding measures guaranteeing labour rights in the context of the pandemic. The Catalan network disseminated several related publications, including an article published by alternative newspaper La Directa (Fayos 2020a) about social demands to make private healthcare public to deal with COVID-19, along with the message: “in the face of the increase in coronavirus hospitalizations, private health care must be put at the service of the common good! That's why we ask for a #SocialShockPlan” (XES, March 17, 2020).

Other examples include the cooperative funds for social and health emergencies (#FonsCooperatiuESS), aiming at providing financial support to solidarity initiatives in need,[8] and a rent strike campaign demanding “rent suspension, now!” (#SuspensionAlquileresYa): “

Housing is not a business, it is a right and we will defend it. If the State government does not react in time and you can’t pay your rent in April, join the rent strike! http://suspensionalquileres.org” (XES, March 30, 2020).

Other campaigns, actions and manifestos followed, such as one in support of farmers, calling for a change in the agro-industrial food production system to meet the needs of peasants and rural territories. In early May, the network released an Action Plan for the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) with proposals for concrete measures aimed at the public administration (XES 2020b).

4.2.2. Communicative Action

The majority of publications located in the intermediate circle of the radar (communicative action) are from XES (33, compared to 9 publications by Cresaçor).

The sharing of information content by XES is very common (roughly 30 of all 86 publications analysed), but – unlike the government bulletins released by the Azorean network, often accompanied with generic #StayHome, #KeepSafe, #EverythingWillBeAlright hashtags – the emphasis is on independent and alternative media that present other visions of the world, and that often reinforce the importance of the work of the network itself, giving voice to its members, its initiatives and partners, thereby standing between communicative action and praxis communication.

In the case of informative content categorised as communicative action, we find media articles around topics that propose new understandings about world views, namely degrowth, the North-South divide, migrants’ lives, feminist economies, ethical banks, and other issues that are not free from conflicts and contradictions, as shown in the example of a news report (Fayos 2020b) on precarious labour in supermarkets, which was shared by XES along with the following message:

We defend a model of commercialization that is far from that of large supermarkets, but we want to show all our solidarity with the workers who these days are overexposed to the contagion without adequate protection. #SolidarityPandemic (XES, March 26, 2020)

Mobiliser content reflecting communicative action includes the promotion of campaigns by external sources to raise computers for children without access to them, food aid, support for tourism (through a “don’t cancel, postpone” campaign) and an initiative by “150 Civil Society Organizations from dozens of countries calling on the World Bank and IMF to #CancelDebt to enable countries in the global South to face the crisis caused by Covid-19” (Cresaçor, April 7, 2020).

Halfway between the mobiliser and the listening axes we find a communicative action by XES with the announcement of the network’s “social balance” campaign of 2020, in the preparation of the annual report of the Social Market of Catalonia.

The sharing of resources reflecting communicative action refers to educational videos by Cresaçor on how to manage the family budget (with fairly condescending tips such as “be careful with promotions” and “make a list before going shopping”), while XES shared guides on how to deal with the exceptional situation created by COVID in terms of labour rights, as well as literary recommendations from independent publishers on the occasion of the world book day celebration (23 April).

Concerning institutional content categorised as communicative action, there was regular dissemination of activities organised by XES or by its members (seminars, workshops, training, fairs, and crowdfunding campaigns). XES also announced the admission of seven new members during the period under review, publicising the websites of the different organisations together with a brief note on their activities (organisations included a transformational communication agency, an association for female empowerment and job integration, an outreach vegetarian cuisine project, a popular school, and a new web development cooperative). Cresaçor also disseminated information about its members in two publications, listing a batch of around 10 organisations (half of which were of a religious nature) with a call to buy their “products with values”.

4.2.3. Communication Practice

In the case of Cresaçor, about half the published content (34 of 77) refers to communications from the Regional Government of the Azores or from other public authorities, essentially on governmental measures related to COVID-19 and therefore standing on the outer radar circle, mostly between the information and the institutional axes. In terms of resource sharing, Cresaçor (re)published notices about recruitment and public tenders, teaching materials and social support hotlines. Listening content was rare, but existed in the form of a survey of owners of 3D printers for the manufacture of protective materials and a survey for the acquisition of virtual reality equipment. With regard to mobilising content, campaigns were mentioned to raise goods (protective masks) for social institutions and a challenge to recreate culinary recipes as a way of “valuing the Azorean sea”.

In the case of XES, only two posts are located in the outer circle of the radar, categorised as institutional communication practice: the announcement of the cancellation of a XES-organised event (Solidarity Economy and Ecology Days) due to the state of emergency and the promotion of a Solidarity Economy Fair taking place remotely at the end of April 2020.

4.2.4. Thematic Synthesis

The analysis of content disseminated by solidarity economy networks in Portugal and Catalonia during the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrates that there is an ethico-political character inherent to communication that allows us to distinguish between mere instrumental practices and emancipatory praxis communication.

In times of a pandemic and health crisis, the content disseminated by these networks addressed issues of (1) the broader society and economy, (2) rights and public policy, (3) calls for solidarity, support and financing, and (4) the ecosystem each network belongs to, giving visibility to their concrete practices. However, the analysis reveals two fundamentally distinct approaches which have implications on the transformational potential of their communications.

To synthesise the results of the content analysis, we proceed to contrast these two antagonistic approaches for each of the four main broad themes covered by both networks – knowing that COVID-19 and the health crisis constituted the cross-cutting theme that ran through the entire period under analysis.

Instead of acting as an echo chamber of official data and press releases from authorities about COVID-19, praxis communication meant delving into the complex root causes of the pandemic, linking the health crisis to macro socio-economic and political issues, and providing a critical view on the global neoliberal market economy that is draining the planet’s resources and exploiting the lives of people and nature for the sake of capital accumulation by the few.

Both networks address themes and problems of economy and society (1) through content that reflects perspectives on the current situation, the socio-economic system and its links to political and environmental issues, whereas mere communication practices tend to share uncritical mainstream world views (without ever articulating the word ‘capitalism’). However, praxis communication additionally provides information that promotes critical thinking about current modes of production and consumption, while illuminating alternatives that already exist in order to advance a better life in the pandemic and beyond, such as mutual aid initiatives and agroecological food supply chains.

Each network also assumes a different position regarding rights and public policy (2) through content that reflects political action demanding – or legitimising – governmental measures and that proposes a more or less transformational vision of the economy and society. Whereas praxis communication mobilises the collective construction of political proposals that respond to the needs of network members and partners (sometimes calling for civil disobedience, as in the case of the rent strike campaign in Spain), non-transformational approaches assume the inevitability of circumstances, hoping that “everything will be alright” (Cresaçor, March 24, 2020) and reinforcing the status quo.

Calls for solidarity and support (3) in response to the COVID-19 crisis, including organising responses to financial needs, also follow very distinct approaches. Whereas praxis communication puts the emphasis on mutual aid, cooperative financing, “resistance boxes” (XES, April 5, 2020) and crowdfunding campaigns, a conformist approach tends to reflect a language of charity, assistance and institutional aid. Where the second asks for volunteers, the first mobilises militancy.

Lastly, making the ecosystem visible (4) goes well beyond the promotion of “products with values” (Cresaçor) and other market opportunities. Praxis communication aligns theory and practice by making visible the concrete practices of solidarity economy that already exist in territories providing real socio-economic alternatives, while amplifying the voices of autonomous organisations who well know how to explain what they do, and how and why it is important for the desired socio-economic transformation.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The results reveal very different communicative approaches in each of the analysed cases: from the silence or total absence of communicative practices demonstrated by RedPES to what can be considered, in the case of XES, a transformational communicative praxis based on collective action challenging the structures of power and domination and pointing out ways to overcome them. In Cresaçor we find communicative practices whose transformational nature is lost to the extent that merely institutional views are reinforced, giving little voice to grassroots organisations and associations.

In Catalonia, the network reveals an active political voice that questions the dominant economic model and proposes concrete alternatives, giving collective power and visibility to an established and growing ecosystem that connects nodes and other networks at multiple levels with a common goal: to promote a transformative vision of society based on principles and practices of the solidarity economy. Through manifestos, campaigns, media partnerships, alliances and the multi-reciprocal sharing of knowledge, support and resources, the network nurtures and expands the collective consciousness that supports its mission. Rather than asserting its own institutional voice, the Catalan network is at the service of its nodes, naming its members and reinforcing their voices, often resorting to the use of hyperlinks (tags and hashtags) between social network profiles, demonstrating a strong cooperative reasoning behind its communicative action; that is, the “[aim to create] benefits for all and the collective control of society” (Fuchs 2020, 296). As such, the collective dimension of praxis communication shows that “the logic of the network is more powerful than the powers in the network” (Castells 1996/2009, 193). The network provides its single elements with opportunities not only to affirm their powers but also to connect and reach broader audiences, thus benefiting from a networking logic defined as “the widespread set of connections [...] between elements which, even when they do not communicate directly, are in fact related by a short chain of intermediaries” (1996/2009, 92).

In Portugal, a silent network reveals a lost opportunity to foster the mission embraced. This seems to derive from a weak network dynamic that ignores communication practices as a way to affirm its own collective identity. It reveals a fragmented ecosystem and a diffuse identity concerning solidarity economy principles and practices, leaving us to question whether it is because there are no real practices to communicate, or because there is no networked praxis communication, such that the solidarity economy remains incipient. In general, the Portuguese organisations reaffirm the power of authorities through their communications rather than questioning their domination, seeming to affirm themselves as extensions of the State in the practical implementation of its social policies. In other words, they seem to be closer to a classical social economy strategy of welfare outsourced to civil society organisations, rather than acting as critical political actors demanding reforms that drive back the status quo. In the Portuguese case the dialectical disunity between solidarity economy theory (which is critical of capitalism) and practice excludes their action from the notion of praxis (Bernstein 1979; Gramsci 1970).

In the case of XES, the State and other public authorities are amongst the interlocutors to interrogate and from whom to demand practical actions, but contrary to RedPES and Cresaçor, the Catalan network never serves as a mere vehicle of (re)transmission of the public authorities’ bulletins and actions. COVID-19 has been an opportunity, like so many others, to reinforce XES’s project of an alternative society and economy. Its communicative action can thus be considered praxis communication in the sense that it is based on a dialectic coincidence between anti-capitalist solidarity economy theory and practice.

To conclude, this study takes advantage of the information and communication trail that solidarity economy organisations leave within the digital realm to understand how and what claims for socio-economic transformations are being put forward, but does not aim at glorifying the power of corporate social media nor the illusion of democratised communication they bring about. What is a Facebook post worth, after all? Beyond the scope of the present study, we recognise the pernicious and alienating effects of corporate social media and acknowledge that many interesting and transformative experiences that exist in the field of solidarity economy are simply absent from platforms like Facebook. Could this be the case for RedPES: a silent network online, but transformational in the physical world? The ethnographic work allows us to confirm a coincidence between what these networks are and do and what they say and show in online social networks. Nevertheless, future lines of research could deepen the communication commons also being created by solidarity economy initiatives that are critical of capitalism, as we cannot speak of true praxis and transformation as long as the means of communication remain in the hands of giant neoliberal corporations.